One of my favorite pastimes growing up

was playing through Sierra adventure games again and again and again.

I used to run laps around the fictional Kingdom of Daventry and its

neighboring realms, playing speed runs that weren't really speed runs

in the early King's Quest

games. I had even more fun ripping through time and space as Roger

Wilco in the satirical Space Quest adventures.

Back then, it wasn't so much the challenge of the game that drew me

in—I'd memorized the solutions to all of the so-called puzzles like

the lines of dialogue in a movie. It was fun just going through the

motions, triggering the animation sequences and sometimes having fun

experimenting with all of the goofy ways to lose or die.

So

it's interesting to return to the genre in the present day—even for

a title as distinct as Machinarium.

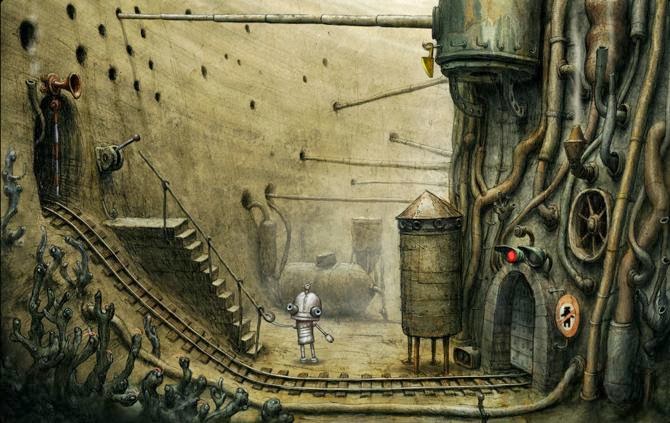

Unlike

the Sierra and LucasArts games of the past, Machinarium

tells its story without text or exposition. Characters communicate

with body language and illustrated thought bubbles. The protagonist

is a down-on-his-luck robot, who finds himself cast out from a

towering robot enclave by a band of unsavory robot thugs. After

sneaking back into the city and succumbing to further gaffes and

blunders, the player must uncover and thwart a nefarious plot against

the denizens of the city.

The story and style of Machinarium actually reminds me of the silent movie era—particularly the American

comedies of Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, etc. I have no idea

whether the influence is direct or intentional, but the plight of the

protagonist does bear some thematic resemblance to that of Chaplin's

tramp. The robot, while plucky and persistent, is clearly on the

margins of this cold-hearted, industrial society, forced to navigate his many setbacks through impromptu tricks and disguises.

Those

are the things I liked about Machinarium.

What I didn't always like was how the game actually played as a

puzzle-solving exercise.

It

seems to me that the game's puzzles tend to fall into one of two

camps. First are the environmental puzzles, the ones that involve

finding clickable objects and inventory items to use and manipulate.

These are the types of puzzles we typically associate with the

classic adventure games genre. The second suite of puzzles were more

like logic mini-games and brainteasers. Surprisingly, I enjoyed the

latter much more than the former. The traditional puzzles rarely make

logical or predictive sense, which means the player will resort to

brute-force tactics—clicking the mouse cursor all over the screen

in hopes of triggering some sort of interaction. In adventure game

terminology, we call this activity “pixel hunting.” It's all the

more frustrating in Machinarium,

because the player is further restricted from interacting with

anything outside of a short radius of the character avatar.

Part

of the problem is the lack of visual cues. At one point in the game I

had solved a pretty challenging mini-game puzzle, which—in my

mind—should have progressed a related environmental puzzle.

Unfortunately, I hadn't noticed a small button on a panel, because

there was nothing that differentiated that button from being anything

other than a simple screw, rivet, or any other pencil-textured circle

in the homogenous background environment.

With

Machinarium, the

developers must have foreseen this, because they implemented their

own in-game hint and cheat system. For most locations in the game,

the player can click on a lightbulb icon that offers a quick hint.

Nine times out of 10, these hints are useless. In that case, the

player can click on a book icon that enacts a strange side-scrolling

arcade game. By winning the game, the player will gain access to a

page that shows a visual representation of the solutions to that particular game screen's puzzles.

At first I hated

the very thought of this. But let me tell you, it was necessary to

go back to that cheat system more than once. And I guess if it's right there

in the game, it's not technically cheating, is it?

By the time I made it to the end of the short game, I was happy that I'd stuck with it. And I'm definitely interested to check out some other games (newer and older) from Czech developer Amanita Design. Based on this title alone, however, I would have to say they are much better at animation and illustration than game design.

By the time I made it to the end of the short game, I was happy that I'd stuck with it. And I'm definitely interested to check out some other games (newer and older) from Czech developer Amanita Design. Based on this title alone, however, I would have to say they are much better at animation and illustration than game design.