- Like an old-school video game challenge.

- Still enjoy doing Mad Libs.

- Are looking for a new kind of party game to show off to your snarky friends.

Wednesday, August 15, 2012

Choose your own Super Amazing Wagon Adventure

Thursday, August 2, 2012

Rapture is us

Wednesday, July 4, 2012

The Trials HD bunny hop and expressive movement

I first learned about the Trials HD bunny hop while watching a YouTube video showing how to get through one of the the extreme tracks. The video tutorial got to the place in the track that had me stumped. Just do a little bunny hop, the narrator told me; push back and forth on the thumbstick and jump. This was easier said than done. I probably tried over a hundred times to get over that uphill bump, but my clunky back-and-forth motions did nothing to help the situation. I gave up on that track for a while.

But there's such a spectrum of available movement, broken up by such minuscule degrees of difference. So often it's the slightest, most sensitive variation in controller movement that makes all the difference between overcoming a track obstacle or losing balance and crashing. And while the most extreme tracks demand the execution of more precise gestures, there nevertheless are infinite ways with which an individual player can move through the virtual environment—be it gracefully or otherwise. Every run through a Trials HD track is like a snowflake in that it can't be replicated. I suppose that's similarly true even for more technologically primitive games, except that other games don't necessarily feel as genuinely physical or gestural. The input/feedback of attempting a virtual jump in Trials HD could be compared to the input/feedback of any real-life physical activity that demands skill and precise muscle control. Ever tried bouncing quarters into a shot glass? Sometimes you'll overshoot; sometimes you'll undershoot. Eventually you'll get it in. And after a while, with more practice, you might start landing it in the glass more often than not.

Thursday, June 28, 2012

5-10-15-25-30

So tomorrow is like my 30th birthday. To commemorate the occasion—and to get something published on my blog for the month of June—I decided to put together a brief retrospective. Here is a snapshot of the games I remember playing at each of the five-year intervals of my life. (I've seen something similar over at Pitchfork.)

So tomorrow is like my 30th birthday. To commemorate the occasion—and to get something published on my blog for the month of June—I decided to put together a brief retrospective. Here is a snapshot of the games I remember playing at each of the five-year intervals of my life. (I've seen something similar over at Pitchfork.)Sunday, May 20, 2012

Wonderputt - thinking around the box

When I was a first-semester freshman in high school I took a drawing class. It was the only art class I took during my entire four years. This was back when I still had tentative career ambitions to become a graphic designer.

There was one assignment I remember in which we had to draw an abstract isometric picture—a kind of jumbling together of boxes and rectangular prisms. The idea was to create something figurative from these bland three-dimensional renderings. It felt similar to a Rorschach test—interesting from a psychological perspective to see what different students saw in a mass of boxes.

A friend who was also taking the class drew his initial piece and immediately envisioned a gun. He rendered his final drawing as a complex weapon resembling an Uzi. It was interesting. Very utilitarian.

I had a more difficult time with the assignment. I looked at my initial sketch and didn't see anything practical at all. Quite the opposite. The best I could envision was a futuristic, utopian cityscape, or rather just a small block of a fantastical (completely impractical) urban environment. I made little shops and buildings out of the blocky shapes. I drew in people walking through the alleys, one guy pulling money out of an ATM.

I was reminded of that 15-year old drawing exercise while playing Wonderputt, a web-browser game developed by Reece Millidge of Damp Gnat Ltd. As much a piece of interactive art as an actual game, Wonderputt presents a surreal isometric landscape as the backdrop for a five-minute point-and-click putt putt adventure. Its 18 holes are linked together by a series of quirky animation bits; the little yellow golf ball travels by balloon, submarine and all manner of imaginative transport. It's a delightful sight to behold as the static backdrop unfolds, reveals new layers and otherwise comes to life with each successive hole.

The game itself plays handily and functions more like a virtual billiards game than golf, in that it's all cursor-based. Position the cursor in a certain radius around the ball and a trajectory arrow will appear. The thickness of the arrow, which changes with the cursor's moment-to-moment distance from the ball, indicates speed.

Wonderputt really is the perfect name for the game. There are no clubs, and while the course itself takes inspiration from miniature golf with its banked surfaces and puzzle-like setup, these holes abandon the notion of traditional putting greens altogether. But it's still a type of golf game at heart, a golf game with a generous standard for par (I was already 16 strokes under after my second time through). Getting a bogey triggers a playful chicken cluck. A birdie activates a pleasant chirping sound. And putting for an “albatross”—one better than an eagle in the land of Wonderputt—awards the player with a victorious squawk.

A cursory peak into the background of the developer reveals some interesting information. Prior to making Wonderputt, creator Reece Millidge had developed a very similar experiment of a game called Adverputt. Just as the name implies, this browser game mixes commercial branding with putt putt golf, with each hole individually sponsored by a different advertiser. While a decidedly colder experience than Wonderputt—not necessarily for the hyper-advertising but more for its comparative lack of visual and auditory character—it's mechanically the same game and an intriguing idea. He even made a micro version of the game that individual companies can use on their own websites, plastering the small game world with their own name and logo. He strikes me as a pretty innovative guy. You can read a quick interview with the developer at Gamasutra.

Needless to say, that whole visual art career path didn't quite happen for me. If it did, or if I had the technical talent to develop small games myself, I'd like to think I would be creating things like Wonderputt. Ever since I was a kid I've been drawn to elaborate, visual-physical contraptions. I loved miniature golf. I swooned over marble mazes and labyrinth games, even the digital ones (a lá Marble Madness). There's also something aesthetically satisfying to me in the conceptualization of basic isometric design as an interactive space. So it's easy to see why Wonderputt and I really click.

But enough about me, you should really check out the game (such as here). It's free. It's fun. You might be as surprised as I was to see how advanced and polished a modern web browser game can be.

Saturday, April 28, 2012

On the List — Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell

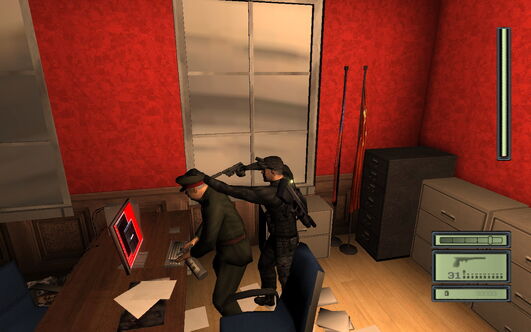

I am a fan, however, of the Tom Clancy's Splinter Cell video game franchise, which began as an original Xbox title back in 2002, developed by Ubisoft. In the game the player assumes the role of Sam Fisher, a Navy SEAL covert ops veteran whom we can probably assume has been through some serious shit in his day. Fisher has been called back into the field, recruited as the titular one-man “splinter cell” for the new ultra secret Third Echelon initiative within the National Security Agency. The idea behind the initiative is to gather info and intelligence from the most sensitive of around-the-world locations by means of physical infiltration and a compartmentalized support network of hackers, handlers and so forth.

The NSA basically needs Fisher to sneak into a former Soviet-bloc country to investigate some strange political shenanigans and the ominous disappearance of two CIA field agents. The information he uncovers has immediate, global consequences. Fisher then hops from country to country to track down new targets and throw water on all kinds of political living room fires that spring up from the fallout.

What the player experiences is a finely tuned stealth action video game, most of which is spent crouching among the shadows, trying to get from one place to the next without being noticed or shot at. Obviously, this is not always easy, causing the player to rely on a repertoire of cool takedown maneuvers and a limited inventory of techno gadgets and weaponry—including sticky cameras, some grenades and a silenced combat rifle. Needless to say, more than a few unlucky or deserving bastards will end up knocked out or rubbed out for being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Taking a cue from the likes of Deus Ex and I'm sure other predecessors, Splinter Cell succeeded as a game that encouraged a certain level of player choice and technique. A scrupulous player was free to put in the extra effort to minimize fatalities and/or confrontations. The more speed-minded player could perhaps afford to run through an area with less caution, soaking up the bullets and simply healing with medical kits later on. Stealthy progress depended, in part, on the speed and sound of Fisher's movement, which the player controlled by applying degrees of pressure to the controller's analog stick.

Similar to games in the Tony Hawk's Pro Skater series—wherein an otherwise standard urban environment will be designed around the fantastical concept of grind-worthy edges and smooth, concave ramps built into virtually every utilitarian structure—the Splinter Cell games present a type of exaggerated environment suited to the mechanics of the game's genre. Most of the settings employ a contradictory combination of high-level security (patrolling goons everywhere) and incredibly poor lighting. The very halls of the CIA headquarters, for example, contain more predatory blackout spots than a mall parking garage.

Playing Splinter Cell invariably causes me to imagine a scenario in which Sam Fisher has to pass through my apartment at night while I'm at home performing some random task, like cutting an onion in the kitchen or folding my underwear in the bedroom. What path would he follow in order to pass through undetected? Or would he more-than-likely just grab me in a choke hold and pull me off into some dim corner of the room? Creepy!

These aren't my only questions. Sometimes, after finishing a level, I have to wonder ... what happens later? What happens in the hours after Sam Fisher has blown the proverbial taco stand and is back at home, drinking his morning protein shake, nagging his daughter to get out of bed for school? What happens when all of those guys who got knocked unconscious and dumped in storage rooms halfway across the globe start to wake up? Surely some of those dudes sustained physical injuries, if not brain damage! Are they going to be okay? What kind of a conversation do these baffled individuals have as they stumble groggily around trying to find one another, or when they start to sort out the living from the dead? What happens to the living guys who wake up underneath the dead guys because there wasn't any other convenient place for Fisher to quickly stash the bodies? Double creepy!

One narrative element I find interesting is the between-mission cutscenes, shown as quick snippets of TV news reports that sometimes present a revisionist spin on the events related to all of Fisher’s recent sneaking around. There's a moment at the end of the game when Fisher, watching a televised speech with his daughter, allows himself an amused chuckle or two as the president of the United States credits the spirit of “American tenacity” for what Fisher has almost singlehandedly accomplished behind the scenes.

At one point during the second level, Fisher’s remote handler Irving Lambert warns Sam about a military colonel approaching his specific location inside a foreign embassy building. “That’s detailed intelligence,” Fisher replies. No kidding! Sam Fisher is no idiot. He’s used to taking orders on little to no information, a so-called “need-to-know basis” if ever there was one. But, for God’s sake, what else are the folks in Washington seeing that we're not? And who's calling the shots? At multiple times in the game Lambert gives the call on whether Fisher is authorized to use lethal force, depending on the political stickiness of the situation. Lambert is sometimes explicit in telling Fisher his mission has not been officially approved by the Joint Chiefs. I'm sorry, did you just tell me we're working outside the approval of the Joint Chiefs? Suddenly, the idea of staying hidden all the time, of turning out the lights on everyone around you, becomes a much larger symbol. By the end of the game we may be wondering if the president himself has been privy to what's really gone on. Such is the way of things, I suppose, in the Tom Clancy universe. Just good fiction, right?

Images were borrowed from splintercell.wikia.com.

Monday, April 16, 2012

If necessary, use words

King's Quest was an interesting type of game that was both a graphics- and text-based adventure. In it the player moved the character avatar around a set of static location screens using either keyboard directional buttons or by clicking with a mouse cursor. This, however, was purely for navigational purposes. The primary system of player input was handled via written commands that the player literally would have to type into existence.

If a player walked up to the castle doors, they would have to type “open door” to actually open the door and proceed. If the player wanted to speak to the king, they would have to type “speak to king.” Later on in the game these text-based commands became a little more puzzling. The player might wander into an exterior environment and have to type something like “look at room,” a basic command that usually would provide a rudimentary description of the environment immediately depicted on-screen. This visual description might even hone in on a particular object of player interest—perhaps a particular rock that required pushing or a tree to climb.

This system of text-driven input had its roots in earlier games such as the Zork series—the first of which were text-only adventures—and carried over into other adventure games for several years until pretty much the entire adventure game genre switched over to a point-and-click interface model. Instead of typing commands the player would select from various cursor icon types, each representing a specific type of action—an eye cursor for looking, a hand cursor for touching or taking objects, and a dialog cursor for speaking to people, things, etc. Other games employed similar systems, and they worked rather well for several more years. Then the adventure genre mostly disappeared.

This past January I downloaded Boxer, an awesome DOS-emulator program, onto my Macintosh computer so that I could theoretically go and play, among other things, a bunch of those classic Sierra On-Line adventure games from back in the day. The first (and so far only) game I went through was a game called Quest for Glory: So You Want to be a Hero, which I'd played to completion several times as a kid on our Macintosh Centris 610 computer.

I think the entire Quest for Glory series (there were five original games in the series released between 1989 and 1998, as well as one remake) deserves a writeup all its own, but I'll just mention a couple noteworthy points. The Quest for Glory series was an early and rare example of an adventure and role-playing game hybrid—arguably heavier on the former type of game. Long before BioWare's Mass Effect series did the same, the Quest for Glory games allowed the player to import their saved character file from one installment to the next, with all of that character's built-up statistics transported intact. Alternatively, one could create a new character file for each game, selecting from three optional character classes: fighter, magic user, and thief.

The version I played through this past January, same as the version I played through as a kid, was actually a 1991 remake of the original 1989 game (which also, incidentally, bore the original series title Hero's Quest, changed to avoid copyright infringement with the HeroQuest board games). Whereas the original game was a 16-color adventure with a text-parser input system, the remake was redone with completely redrawn 256-color graphics and a point-and-click user interface.

One aspect of the (remake) game that I had always enjoyed was its system of dialogue with non-playable characters. In all of the other Sierra adventure games I'd played, there really was no dialogue system at all. Speaking to other characters—whether initiated via text- or cursor-based command, depending on the particular game—was functionally no different from looking at something or performing any other type of action. In this Quest for Glory remake, however, clicking the dialog cursor on a character brought up a menu of dialogue topics, sort of an early dialogue tree. Selecting one topic might cause that character to provide background information on related subjects, sometimes bringing up a new sub-menu with some of these new topics. It was an excellent vehicle, I thought, for communicating story and information.

After going through the game again, I was hoping to finally transport my character over to the sequel, Quest for Glory II: Trial by Fire. This was something I never got to do as a kid, because that game—as far as I'm aware—was never released for the Macintosh.

My original plan was to play through the sequel using a 2008 fan-made remake version from a group called AGD Interactive. Like the original Quest for Glory (or, rather, Hero's Quest), Quest for Glory II had incorporated 16-color graphics and a text-input system. The fan remake was a redeveloped game with improved graphics and a point-and-click interface. Unfortunately, I was unable to get the game to run on my OSX computer. I also couldn't run it on my dinosaur PC laptop. At that point my only recourse was to try and run a pirated download version of the original Quest for Glory II game, which didn't end up working on the Mac but luckily ran using DOSBox on the PC laptop. Whew!

(I normally wouldn't condone using pirated software, but in this case there currently is no digital distribution service, such as Good Old Games, for purchasing the Quest for Glory titles. And there's absolutely no guarantee I would have been able to run the game through any kind of legitimate used e-Bay copy.)

I'm actually glad I played the original Quest for Glory II in all of its original clunkiness. Again, I wish I could do better justice to this game with a more in-depth writeup. Maybe in the future. It would be very hard to recommend playing this game to anyone I know. It's primitive. It had some very strange design choices. Modern game players, with or without the background experience in old adventure games, would need the patience of Job to get through it. Even so, it's a fascinating kind of game. I quite enjoyed it myself.

If anything, playing the original Quest for Glory II made me a newfound believer in the potential of text-based player input.

Recall what I was just saying about the cool dialogue menus in the remade Quest for Glory I? At first I was baffled about how one was supposed to initiate dialogue in Quest for Glory II. If I were to type simply “speak to [character],” nothing would happen. Then I looked at the program menus and noticed a keyboard shortcut for the text prompt beginning “ask about.”

Instead of just typing “speak to [character]” and being spoon fed a dialogue tree with pre-selected conversation topics, the player has to be specific regarding what they want the character to discuss. Functionally, gleaning information from a character might play out very similarly to the dialogue tree. Perhaps in asking about a particular city the character will mention the name of a person. Ask about that person and the character will divulge more specific information. But it's up to the player to make those connections and associations to new topics. Better yet, as the player progresses through the game and learns about new potential conversation topics from other sources, the player can go back to earlier characters and see if they have anything to say about that new topic. Sometimes they do.

I'm sure if Quest for Glory II were converted to a modern game console there would be some kind of collectible achievement for activating every available dialogue window. In essence, there's nothing necessarily tangible gained from trying to “ask about” every single topic. But the typing system creates a playing experience that really is unlike almost any other. Accessing programmed content with the power of one's intuition is enjoyable. There's something to be said about being able try virtually anything, or of using one's brain power to find the necessary words, for initiating the type of action one might attempt for overcoming puzzles and obstacles. Quest for Glory II and its contemporaries may have been primitive games by today's standards, but I find it somewhat sad how the use of text-based input in games was abandoned.

On the one hand, I suppose this kind of itch for unlimited player input could be partially satisfied through different kinds of table-top role-playing or other community-driven games. I can't speak from personal experience. But I think there's something almost mythical about the connection of the minds between a player and a programmer that has nothing to do with real-time interaction or ad-lib dialogue. This has to do with a game inventor who has put in place a specific framework for responding to the predicted input of an actual user. (On a total side note, I'm reminded of the Foundation novel series by Isaac Asimov, dealing with “psychohistory” and the prediction of mass human behavior.)

When I was in middle school I went through a brief period where I tried programming and designing my own graphic adventure games using a Macintosh authoring system called World Builder, released first in 1986 by Silicon Beach Software (the same company that made the game Dark Castle) and later in 1995 as freeware. The program allowed users to create original adventure games using static black-and-white graphic screens and text.

This was an amazing piece of software, and there were a lot of interesting, albeit obscure, games created because of it. What was really neat was being able to create my own vector graphics in Adobe PageMaker and then copy and paste them into the World Builder graphic design engine. Even better, using the World Builder tool introduced me to a mode of simple computer programming, using a custom language similar to BASIC. For each static location I would have to create lines of codes that would correspond to player text prompts. For example, “IF a player types 'a', THEN 'b' happens.” I even figured out a way to use this programming to implement basic animations, such as a bird's-eye view of bungee jumping from off a bridge toward a river below (man, that segment was fun to make).

It was fun to try and think about the different things a player might type while playing and program specific feedback to that potential behavior. I also learned it's just as much fun to create special triggered events for even the more obscure types of actions that a player might attempt—a sort of reward for intrepid and like-minded individuals. Unfortunately, I never did manage to create a finished product, nor did I have any actual players test my bedroom project. What I did manage to get underway is likely still stored on our family's antique black-and-white Macintosh somewhere in my parents' attic.

I myself am not yearning for a resurrection of traditional adventure games (although, oddly enough, there may actually be somewhat of a demand for it … see here and here). But I do think there is potential in the idea of modern text-based game mechanics, particularly in the android/iOS market where a nifty keyboard is already right there.

On a basic level, it's actually just plain fun to see one's words brought to life in a game. Examples? I've heard people get to name their own weapons in The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim. That's awesome! There's also a neat and completely throwaway feature in Team Ninja's Dead or Alive 4 fighting game. The game copies the text from the user's Xbox 360 profile motto and displays it on various electronic billboard banners in some of the fighting environments. It's pretty funny when beginning a virtual fight in a large packed-housed stadium and seeing my limited-character motto (“4 me 2 P@@P on”) displayed in gigantic moving text all around the enormous room.

On a larger scale, I wonder what might have happened if the idea of text-based commands had not been so completely abandoned. What if that type of system had survived, adapted to and evolved with modern games? What if we had a type of game today—like the Mass Effect series—that incorporated the individual choices of the player on an even more sophisticated level? What if these games involved complex and dynamic consequences resulting not just from the choices directly presented to the player but from the ones the player came up with independently?