This past month I finished the original

Silent Hill game, and for weeks now I've been trying to write something about it. Unfortunately, no good ideas were coming to me. So in order to at least purge this game from my system I've decided to just throw words on paper. I don't know if any of it sticks.

I will just say that it's a very interesting game, far from perfect but almost better because of it … if that makes any sense. Anyway here are some of my impressions.

Start Me Up

Silent Hill

Silent Hill has one of the weirdest

opening cinematics I've ever seen. I'm talking about the film segment that plays before the main menu comes up, before the player even starts the game proper.

The first thing that stands out is the song by Akira Yamaoka. It's got this haunting mandolin over guitar (I think) that quickly turns into something from a James Bond theme that soon gives way to a bit of a spaghetti western feel. However you want to describe it, it's a good track.

The accompanying CG montage, although it doesn't initially make any contextual sense to a beginning player, is pretty interesting as well, even more so after you finish the game and realize that most of the sequences do not appear anywhere in the actual game. It's only later that you go back and begin to try to analyze what some of the images are referring to—a mansion in an open landscape, a nurse in a physical altercation with a man. The sequence does a good job of priming the brain for what will end up being a rather puzzling experience all the way through.

I Saw Her Standing There

After the opening montage, the game begins with an equally great playing segment. Your player character Harry Mason wakes up in a wrecked car. His seven-year-old daughter is missing. You emerge from the car to find yourself in what appears to be an abandoned town. It's foggy, gray. Snow is falling. You step forward.

You see a figure standing in the distance, partially submerged in the thick fog. Is it your daughter? Just as you approach her she runs away. You run after her, follow her trail into a strange alley. You pass through a gated fence with a “beware of dog” sign, and there's blood on the ground—and a fleshy mess—but from what, or whom? That doesn't look like the work of any normal dog. You keep going, and the alley becomes narrower. You pass through another gate and suddenly it's dark as night, so Harry pulls out a lighter (it might be a match). There's a crashed wheelchair with the wheels spinning. What's that about?

As you continue on the camera angles become all wonky and discombobulating, almost enough to make you want to throw up. There's blood everywhere, then some more scraps of flesh. You see some kind of skinned, crucified body hanging on barbed wire. Then, just as you try and flee in terror, these gray childlike monsters close in on you and stab you to death. And that's just the first four minutes of the game!

Deja Vu

It's almost impossible to talk about Silent Hill without talking about Resident Evil. It's no secret that the Silent Hill franchise was game developer Konami's late response to the survival horror success of Capcom's zombie series. The mechanical similarities are undeniable, from the tank controls to the puzzle solving to the mazes of locked doors and monster-infested corridors. And yet these borrowed mechanics—and their familiarity—serve the game rather well, because at the end of the day Konami ended up making a very different type of game. And it's the similarities that help make Silent Hill's distinct flavor all the more apparent and appreciated.

I've heard a lot of people describe Silent Hill as a more psychological game than Resident Evil. That's true. Silent Hill is a much darker game. Whereas Resident Evil (or BioHazard as it's known in its native Japan) deals with physical mutations and evil corporations, Silent Hill is straight up about the occult and demonic forces.

But that's not the only distinction. Whereas Resident Evil had a very keen focus on strategy, resource management, and the sheer challenge of getting from one claustrophobic corridor to the next, Silent Hill eschewed much of that strategy-based focus in favor of a more streamlined playing experience. Yes, there are ammunition supplies to conserve, but there is no time wasted in having to decide which weapon or ammunition type to carry around at a given time.

Silent Hill is roughly divided into two types of playing maps. There are the open-world segments, in which the player must navigate the large open streets of the town. Then there are what I would argue are the more Zelda-like dungeon areas (an elementary school, a hospital, etc.) that play more like a traditional Resident Evil map. And yet even in these dungeons, the game manages a kind of pleasant flow and progression. There's a method to getting around, which is simply to try and open every door you can, and the correct path becomes apparent through a process of elimination.

The puzzles in Silent Hill are a lot more cryptic than those in a Resident Evil game. Often they involve deciphering clues and hints delivered through pieces of text. There are certain aspects of Silent Hill puzzle solving that feel like a throwback to traditional text-based or point-and-click adventure games.

But one of the most notable (and yet subtle) differences between the two games is the combat. If you were to juxtapose Silent Hill's combat to that of Resident Evil—which has always been somewhat clunky in its own right—the latter game is downright agile in comparison. It's a slow and awkward sight to behold when Harry swings his lead pipe at an enemy, a maneuver that simultaneously leaves him vulnerable to counter attack. His shooting is not very good when not delivered at near point-blank range. And yet these same handicaps reinforce the narrative reality of the situation. The protagonist in Silent Hill is no action hero, and he never feels like one.

Obscured By Clouds

The early days of 3D were not always pretty. The 32- and 64-bit systems that ushered in a new era of real-time 3D rendering did so almost at the expense of the hardware itself. Sometimes it came down to a matter of what the developers were willing to sacrifice—realism or performance. Games with a lot of environmental detail and surface textures were more difficult to render due to memory and processing constraints. Thus, developers flooded their games with this environmental fog that masked the embarrassing effect of scenery objects suddenly “popping” into the view of the player at a relatively close proximity.

Silent Hill was probably the first (and perhaps the only) game to really use that technical constraint to its advantage (it almost worked in Turok: Dinosaur Hunter, but not quite). Players wandering through the town of Silent Hill can't see more than about 20 virtual feet in any direction. This in and of itself was nothing new to games in 1999, but in most games this posed a number of problems for the player.

Not being able to identify any significant landmarks in a 3D game world makes it difficult to know where the player is at or where they need to go. Fortunately, Silent Hill incorporates a very helpful mapping system. Harry has a map that he marks on with information as he explores. If a particular street proves unnavigable, the game automatically makes a scribble on that area of the map for future reference. And by pulling out the map, an arrow points in whatever direction Harry's body is currently facing.

And it's usually a good idea to know where you need to go and get there quickly, because wandering through Silent Hill is never safe. There are all sorts of demonic, Lovecraftian monsters lurking around. Due to the fog, it can be almost impossible to know where they're at or how close they are. The Silent Hill developers only partially solved this problem. First of all, Harry receives a portable radio that inexplicably emits a static noise whenever a monster is near. That gives the player a clue to watch their step. But the problem of not seeing the enemies, in this case, isn't such a bad thing. As with the feeble combat, the limited seeing distance creates tension and dread.

Shine A Light

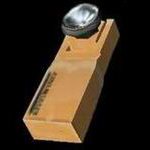

There's another tool in Harry's inventory that adds yet another interesting component to the playing experience. It's a flashlight that Harry clips to his chest pocket, which he automatically turns on during the nighttime (or

Otherworld) segments.

I didn't realize until about a third of the way into the game that the flashlight is really an optional device. During the daytime segments, there is no need to use the flashlight and it doesn't come into play. But when it gets dark, Harry actually has the option to turn the flashlight off. While this might seem like an idiotic thing to do, it can be used to the player's advantage. Even though the player will have a harder time spotting the creeping monsters, the creeping monsters will simultaneously have a harder time spotting the player.

During many of the game's open-world segments I often found myself simply turning off my flashlight and running through the darkness as fast as possible. Even though there were monsters nearby, my strategy was just to run and run and hope for the best. It's kind of the equivalent of a child who hears a strange bump in the night and pulls the covers tight over their head, trying to block out the fear by refusing to pay attention. By running blind, of course, the player eventually loses sense of direction. As a rather smart move on behalf of the developers, the game does not let the player consult the map unless the flashlight is turned on. In doing so, however, the player risks giving up their location to whatever enemies are nearby.

Sad Lisa

Silent Hill feels like an incomplete game, almost like a beta test or a clever experiment for a game. Even after the credits have rolled, regardless of whether the player receives either a “good” or “bad” ending, there's really no sense of closure. From a narrative standpoint, it's not readily apparent what just happened at all—logically or otherwise.

We know there is a strange cult in town. There may be some drug trafficking involved. And there may be a crazy woman who sacrificed her seven-year-old daughter in a fire as a means of ushering in the birth of some demonic entity. But if the real “story” of Silent Hill exists somewhere as a complete and delicious meal, then the game treats the player more like a dog under the table than a proper dinner guest. We like the scraps we're given and we want more.

The Harry Mason character is more blank slate than Deus Ex's J.C. Denton, an empty vessel meant only to represent the point of view of the player. It's the strange people Harry encounters that are far more interesting.

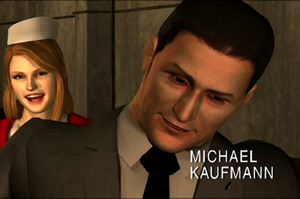

The most fascinating is Lisa Garland, a hospital nurse who appears in the game's otherworld setting. She's a desperate character, and in the end a tragic character. The first time you see her, she clings to Harry with startling affection (via CG cutscene). As Harry drifts in and out of consciousness between the day world and otherworld, there's a subtle relationship that develops between the two characters.

On the one hand she acts as a kind of anchor. Amidst all of the freakish encounters, Lisa is like a calming and familiar presence, a confidant of sorts. And yet, why is it that she only appears in the nightmarish otherworld reality? Even as Harry makes an offer to try and protect Lisa, she herself appears to be strangely anchored to that hellish hospital where other zombie-like nurses wander around the hallways in a fiendish stupor. Harry's final encounter with Lisa immediately goes down as one of the most oddly gut-wrenching moments of any game I've ever played. Game artist Takayoshi Sato, who single-handedly created all of the game's CG cutscenes, had an incredible influence over the mood of the game, and his scenes with Lisa Garland are by far the most memorable and effecting.

David's Song

Do you like David Lynch? If so, this is the game for you. Silent Hill is absolutely dripping with his influence (or at the very least wringing juice from a cut of the same fetid cloth).

Do you like David Lynch? If so, this is the game for you. Silent Hill is absolutely dripping with his influence (or at the very least wringing juice from a cut of the same fetid cloth).

Consider the audio onslaught of Eraserhead, the strange industrial noise that permeates the entire film. Silent Hill creates a very similar soundscape, from the diegetic radio static to the sometimes grating and unnerving musical score. Even the game's visual world—as it transforms into an alternate nightmare version of itself, all rusty metal and dystopian decay—shares a similar grotesqueness to the wasteland set pieces of Eraserhead.

Some parts of Silent Hill feel very reminiscent of Twin Peaks. Think of Silent Hill as the quiet small American town with a dark, mysterious undercurrent. There's a CG reel in the closing credits of two game characters sway dancing rather hypnotically and suspiciously, which I'm almost convinced is a nod to characters like Audrey Horne or the "Man from Another Place" dancing in Twin Peaks. But even the setup of Silent Hill has some parallels to the TV series. Twin Peaks begins with the mysterious murder of a teenage girl and an outsider who comes to the town to investigate. Silent Hill begins with an outsider coming to investigate the disappearance of his daughter. It's the plot device that sets all of the madness to follow into motion. One of the game's creators (not sure which one) has been quoted as saying that the name Cheryl Mason (Harry's daughter) is a reference to Sheryl Lee, the actress who played Laura Palmer in Twin Peaks.

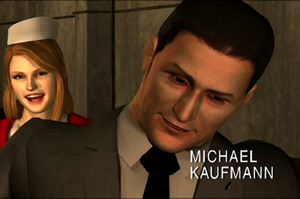

Then there are the themes of duality, the Lost Highway ambiguity of what is real versus what is a hallucinatory nightmare and the gradual merging of the two, to the point that there is no longer any real distinction. Who is that doppelganger of Harry's daughter? And isn't it interesting how the interrelated characters of Michael Kaufmann and Lisa Garland appear in the same hospital room, only that Lisa appears in the otherworld version of the room?

Basically, the entire game playing experience is akin to the role of Kyle MacLachlan's Jeffrey Beaumont character in Blue Velvet. Like Beaumont, we find ourselves drawn to that darkness, lured deeper and deeper into the knowledge of evil.

Tell Me What You See

There have been a lot of indie titles that have been sporting a retro art style. They look like old 8- or 16-bit games. Nobody that I can think of is touching the look or style of the 32-bit era. Like I said earlier, it was pretty ugly.

But the grainy, pixellated look is absolutely perfect for Silent Hill. The monsters are so much more effective, because frankly, it's hard to tell what they look like. They're more suggestive than representative.

The environmental gore—the fleshy objects, the hanging bodies—leave much more to the imagination than if they were drawn in modern high definition. There are even many sections of the game where the wall textures look like those old ink blot tests.

And I feel that's pretty representative of the entire game. It's open to interpretation.

Silent Hill gets three out of four stars.

Silent Hill gets three out of four stars.

Images were borrowed from silenthill.wikia.com.

Silent Hill has one of the weirdest opening cinematics I've ever seen. I'm talking about the film segment that plays before the main menu comes up, before the player even starts the game proper.

Silent Hill has one of the weirdest opening cinematics I've ever seen. I'm talking about the film segment that plays before the main menu comes up, before the player even starts the game proper. There's another tool in Harry's inventory that adds yet another interesting component to the playing experience. It's a flashlight that Harry clips to his chest pocket, which he automatically turns on during the nighttime (or Otherworld) segments.

There's another tool in Harry's inventory that adds yet another interesting component to the playing experience. It's a flashlight that Harry clips to his chest pocket, which he automatically turns on during the nighttime (or Otherworld) segments. Do you like David Lynch? If so, this is the game for you. Silent Hill is absolutely dripping with his influence (or at the very least wringing juice from a cut of the same fetid cloth).

Do you like David Lynch? If so, this is the game for you. Silent Hill is absolutely dripping with his influence (or at the very least wringing juice from a cut of the same fetid cloth).