UDPATE (3/18/13): There's a slightly better version of this article on Gamasutra. Maybe read that one instead. K thanx.

"On the List" is a series that lets me talk about my favorite video games of all time, games that could potentially end up on a best-of list.

“So you run and

you run to catch up with the sun but it's sinking, racing around to

come up behind you again.” - Pink Floyd

As I get steadily

older, and as I become further poor of it, my time becomes an

increasingly valuable commodity. It seems no matter what I do or

don't do, all of my goals and aspirations outpace my ability to reach

them. It's not often that I think about death itself, but I do think

about approaching middle age. As pointless as it may be, I sometimes

worry now about the regrets of what I might not accomplish in five,

ten, or even thirty years time—assuming I'm fortunate enough to

have them. What's wrong with me, right? Just get out there and live!

I remember when

The Sims came out in early 2000. It was a fun little game about the

pursuit of happiness—from a decidedly first-world perspective.

Create a person or a family. Tell them when to bathe, when to be

social, when to practice a musical instrument. Take care of their

needs and hopefully watch as they progress through the ranks of their

respective careers. And above all, help them to buy and decorate

their house with the coolest stuff. The Sims was genre-pegged as a

life simulator, but I'm not so sure what that means. I think it's a

game that has more to do with socio-economics than with “life”—at

least in the grand sense of the word. Where was the drama, the

everyday anxiety of existence?

In 2007 I

stumbled upon an entirely different sort of game, Shin Megami Tensei:

Persona 3. It was just on a fluke that I played it. Somebody gave me

a hand-me-down Playstation 2 that hardly worked. As sort of a starter

kit, the person who gave me the system also let me borrow this absurd

looking Japanese role-playing game (JRPG). The first thing I noticed

about it was its sleek anime art style, but I really had no idea what

I was getting myself into.

The game centers

on a band of Japanese teenagers who—as with every other band of

JRPG teenagers—must contend with a dark and powerful,

world-threatening force. Unlike other JRPGs, Persona 3 doesn't send

you wandering all over the planet or parading around in big flying

boats. Nor does the final battle take place on the moon. It actually

takes place on the roof of your school.

Something is

strange in the city of Iwatodai. Each night starting at midnight, the

moon turns a sickly green color and just about everyone transforms

into a coffin—literally. The students' high school morphs into a

massive tower fortress known as Tartarus, and a bunch of shadow

monsters start wreaking havoc. For some reason, this Dark Hour does

not affect a select group of individuals, including the main

protagonist, a newly arrived transfer student. These gifted

individuals are the only people who realize the Dark Hour even

exists. Worse yet, this strange phenomenon seems to be causing an

ominous outbreak among the population known as Apathy Syndrome,

whereby people suddenly fall into a numb, vegetative condition. As

such, the protagonist joins forces with his dorm mates who form the

Specialized Extracurricular Extermination Squad (S.E.E.S.). The

group's members have dedicated their nights to hunting the shadows

inside Tartarus, hopefully to vanquish the Dark Hour from existence.

The most

interesting aspect of the game is its structure. Events in the game

take place over a one-year period, with the days and weeks counting

down to some kind of hinted doomsday. Daytime segments play out like

a social simulator. During the weekdays, the player character attends

school, then spends the afternoon either hanging out with friends,

attending a campus club, or doing some other activity around the town

before retiring to the dorm. Then, on most nights, the player has the

option to form a party and go fight monsters at Tartarus. This is the

combat portion of the game, one enormous grind of randomized

dungeons, turn-based battles, and periodic boss encounters.

To say that

Persona 3 takes its time is an understatement. As the game goes on,

various plot twists formulate. New story clues comes to light. The

members of S.E.E.S. undergo their various trials, both individually

and as a team. But most days are just regular days, with the player

deciding how the protagonist will spend his free time.

And it's within

this limited freedom that the game truly shines—as a game. The

choices available to the player present themselves in a largely

scripted fashion. As the hours tick by from early morning to mid

morning, from mid morning to after school and onward, there are

moments that come up. Some mornings the game's focus will narrow in

on a classroom lecture, during which a teacher will be going on about

some subject. If the teacher pops the protagonist a question and the

player answers correctly, that protagonist's popularity rating will

increase. Sometimes the game will give the protagonist the option to

take a nap during a lecture. Whereas doing so temporarily improves

the character's physical condition, paying attention to the lecture

will result in a permanent increase to the player's academic ranking.

A similar choice

presents itself during most evenings. If the player decides not to go

battle during the Dark Hour and retreats to the dorm room for the

night, there will generally be the option to either stay up studying

or go to bed early. These studying opportunities can be valuable for

gaining those academic skills. But getting rest is equally important

for preparing the body for battle during the Dark Hour and for

preventing sickness.

The most

interesting choices are the ones that involve social interactions

with other characters, sometimes forming social links. During my play

through of the game I befriended a fellow track athlete, an eccentric

old couple who ran a local bookstore, a drunken monk at a nightclub,

an MMO computer game player, a little girl in a park, some of my

fellow S.E.E.S. members, and more. Some of these social links are

more difficult to access than others. Certain options will not appear

until the protagonist has reached a certain benchmark in academics,

charm, or courage points. Others are available only through exploring

particular areas of the city at a certain time and day of the week.

Each of these relationships forms a social link that, when leveled

up, allows the player to create more “persona” characters, which

are used like summonings during battle. Some story branches lead to

other story branches.

My protagonist,

for example, had an interesting love life. After going out with a

fellow athlete for a while and maxing out that social link, he

started following a link with a shy girl from the Student Council

Club. When I realized this character was forming a crush on my

character, I decided to stop pursuing that social link. It was a

tough call, especially knowing that by spending time with the girl

she was beginning to overcome her self-confidence issues. Oh well.

Closer toward the end of the game, as my character's stats began to

reach the higher echelons, I suddenly found myself with the option of

pursuing all three of the women in the protagonist's dorm—a pretty

satisfying reward for his persistent leveling. Of course, social

dynamics played a factor. Dating multiple women at the same time

would lead to trouble, and there was probably only sufficient time to

pursue one of the three girls.

But I really kind

of admire how the game stayed true to this rigid design throughout

the game. Unlike so many RPGs that give the player so-called freedom

to explore every last quest and side story to their neurotic content,

here is a game that forces actual choices. A year is a long time, but

not long enough for everything. If the player chooses not to

participate in certain holiday festivities, or to pass up on a

invitation to hang out with an acquaintance, those social

opportunities and potential memories will be lost for good.

I think this

resonated most when it came down to the small daily choices—when to

sleep, when to study, when to go battle. It's something I relate to

every day when I come home from work. What is the best use of my

time? Is it in writing (boosting academics)? Going for a run (combat

training)? Spending quality time with my wife (improving my social

links)? And in this way, the game feels like a much more accurate

“life” simulator than any kind of glorified dollhouse game—as

great as it may be in its own right.

The game's

opening cinematic makes multiple textual references to “Memento

mori,” a Latin phrase that translates to something along the lines

of “remember your mortality.” It also refers to an artistic theme

popular through classical and medieval European history. Painters

would depict still-life images of skulls and skeletons to reinforce

the message—remember that you too will die! Is Persona 3 a

modern-day Memento mori?

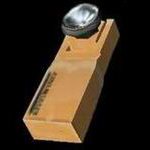

Interestingly,

the opening animation juxtaposes this textual reference with the

game's most iconic image—attractive characters shooting themselves

in the head! This is actually the animation that happens all

throughout the game whenever a character in combat summons a persona.

They do so by aiming a pistol-shaped device called an Evoker at their noggin and pulling the trigger. The characters don't even keel over, but the wispy particle substance that emanates

from the other side of the head is clearly meant to resemble

something much more violent and permanent.

Is this supposed

to be symbolic, the stark reminder of death implied in the “Memento

mori” reference? I imagine that's a part of it. But wouldn't an

image of suicide sort of contradict the implication of that very

reference? I suppose one could argue the game is engaging in a form

of psychological reverse engineering, inverting a dark and highly

suggestive image of giving up in a way that it becomes a much more

positive representation of fighting back. I imagine it's also an

exercise in being subversive for subversive's sake. If anything, it's

provocative, an interesting way to illustrate the undercurrent of

teen angst that flows throughout the game.

Ultimately, I

think there's an even greater irony that relates to the entire

Persona 3 playing experience. For a game that does such an effective

job of reinforcing the seize-the-day outlook, it does an even more

effective job of sucking away one's otherwise productive hours.

Persona 3 is the longest game I have ever played. While I managed to

spread it out over a six-month period or longer, I'm pretty sure my

final play through clocked in at over 120 hours (I made sure to

basically erase the save file from existence as soon as it was over).

I remember being just stunned as the hours continued on past the 50

or 60 mark and just . . . kept . . . climbing. It got to the point

that I had to ask my girlfriend at the time (now my wife) for a day

of solitude to complete the game. I don't think she took the request

very well, but it did the job. I spent probably an entire weekend to

wrap it up, and I still had to stay up quite late to do so.

As I mentioned

once already, one of the game's optional side stories involves the

protagonist playing an online role-playing game. It's bordering on

metafiction. In doing so the protagonist befriends a player who goes

by the name Maya. It's kind of a fun story segment that involves

selecting the dialogue options, which the protagonist types to his

online companion. Maya, in return, types back a bunch of playful

comments, mixed in with all manner of chat abbreviations and

emoticons, and there's a flirtatious little relationship that forms

between the two. It's later revealed that the anonymous Maya is

actually your character's homeroom teacher, who gets like totally

embarrassed when she finds out she basically fell in love with her

student. Persona 3—like so many Japanese games—has its cheeky

moments, little bits of nerd fantasy indulgence. But the funny thing

about that social link is that the option is only available on the

weekends. And by playing the online game, the protagonist spends his

entire weekend playing the game, thus eliminating the possibility of

doing any other activities all day. I swear the game developers at

Atlus must be aware of this ridiculous setup they've created. Here I

am, whiling away my own precious hours role-playing as a make-believe

Japanese teenager who is flirting with a make-believe online game

player—to the point that I have to seclude myself from my very real

girlfriend to keep playing the make-believe game! Obviously, this was

one minor part of the entire game, but it does sort of put things in

an interesting perspective.

Looking back, I

actually think my time playing Persona 3 was time well enough spent.

Not that I ever want to ever go back! This was four years ago when I

was knee deep in a very stressful, life-sucking career as a newspaper

reporter. It was a job that drained so much of my time and energy,

and playing Persona 3 was for a time my mode of escape—not so

different from the protagonist taking a deserved break from his own

exhaustive battle against the Dark Hour to unwind with a video game.

Abnegation, at times, does have its merits.

If you really

think about “Memento mori,” there are two ways of responding to

the message. One day you will die, so get out there and do something

with your life while you still have time! On the other hand, no

matter how important you think you are, and no matter how great or

small your individual accomplishments, you too will one day die. So

what's the point in worrying about everything so much? I'd like to

think there's a balance to be found in between the two, and that

there's a perfect time for everything. I could spend probably a

lifetime trying to find it.

Images were borrowed from megamitensei.wikia.com.

_-_n._23185_-_Socrate_(Collezione_Farnese)_-_Museo_Nazionale_di_Napoli.jpg)